INNOVATION

-

Mariners’ Church, 1955

Mariners’ Church, 1955

-

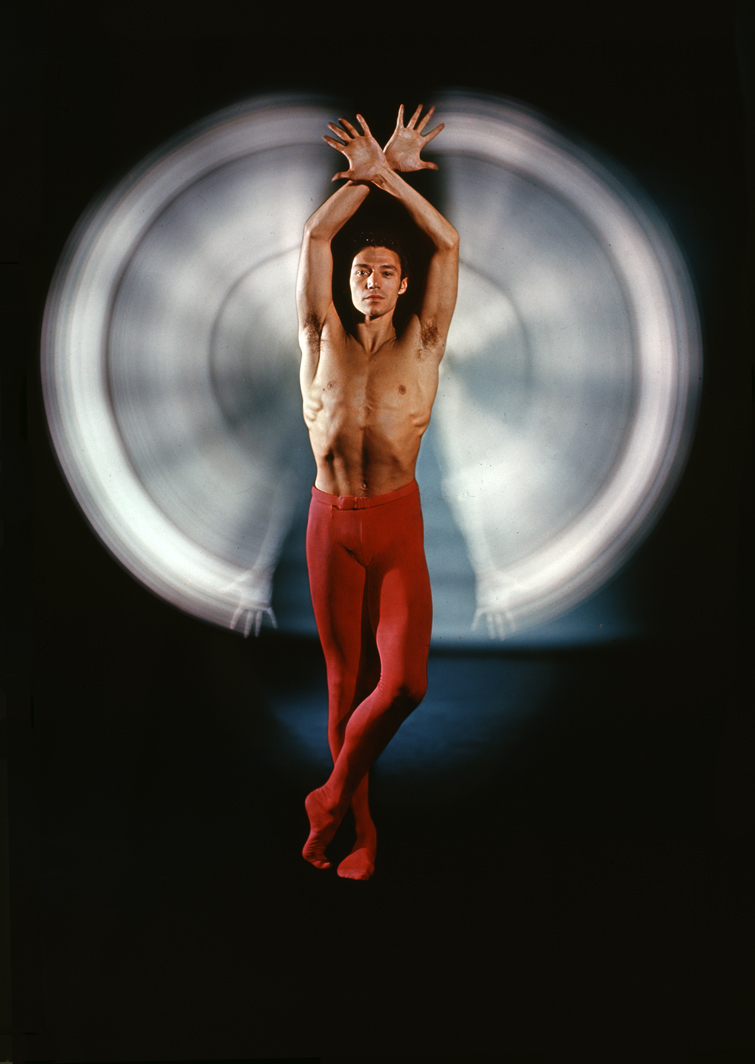

Dance Sonata, 1966

Dance Sonata, 1966

-

Biplane, 1963

Biplane, 1963

Biplane, 1963

Close Close Read MoreThe following excerpt is from Masters of Contemporary Photography Zimmerman & Kauffman Photographing Sports.

Much more in the Zimmerman style was his recreation of the glamour of open cockpit flying. Zimmerman in this instance relied heavily upon remote control cameras and the daring aerial wizardry of pilots Frank Tallman and Paul Mantz, owners of a flying museum in Orange County, California. “Tallman dug up some old flying togs, trimmed with a flamboyant scarf that trailed out of the cockpit and then flew some of the damndest machines, ” Zimmerman recalls. “One was an early Bleriot that was steered by pulling on cables that warped the wings. He headed out over the Pacific in the thing. ”

Tallman put on dogfights with rickety contraptions–a Fokker D- and a Spad–that climbed, dived, looped and spun in mock duels for the benefit of a one man audience and his cameras. Much of the time Zimmerman flew in an LT-1, a strafing aircraft whose machine gun and canopy had been removed so that Zimmerman could hang out with his cameras for an unobstructed view. He was held in by two straps while the slipstream tore at his body, whipped his hair and tried to strip away his cameras. “The best I can say for that old goose of a plane was that it was one of the few times I didn’t get airsick,” says Zimmerman. For all the time he’s spent bobbing on boats or circling in small planes and helicopters, Zimmerman is uncommonly prone to airsickness.

“I used to be able to fill two or three bags easily,” he says. “Happily I’m getting over it. Taking those pills only makes me drowsy. Looking through a viewfinder helps, but when the horizon becomes disoriented and your head is down loading film, while the pilot is in tight maneuvers, it can become quite unpleasant. But if you’re careful and not hurried you can do just about anything. I’m not really fascinated by flying so much as by the extraordinary images it affords.”

To show the antique airplane in its steep bank Zimmerman put his trust in Tallman both as a pilot and a cameraman. They mounted a 250-exposure-back Nikon on the fuselage with the wire to the remote switch running down the joystick. It was equipped with a 28mm lens set at f/16 and 1/15 second to give a blur that would transmit the feeling of a spin. All the stunts were worked out on the ground before Tallman took off. But the amount of light and its direction were uncontrollable. Sometimes Tallman headed directly into the sun; on other maneuvers he would fly out of it. In most aerial photography the pilots are under rigid instructions to fly in such a relationship to the sun as to not vary the eposure. “I wanted him to do everythng and not worry about the exposure, “says Zimmerman. “I was planning on some happy accidents to occur. With a wide-angle lens I knew that even if the sun was in the picture there wouldn’t be enough flare to ruin it.”

Actually the pilot’s original instruction for the picture was to illustrate a roll. The viewer identifies it as such by the clear vortex in the center of the whirling color. Had the pilot executed a perfect maneuver the open tunnel would be on line with the midpoint of the aircraft from nose to tail to ground and would be totally obscured by its stabilizers at the rear of the aircraft. In fact, the pilot executed a slipping roll that placed the eye off-center and in the full view of the camera–an other happy accident.

-

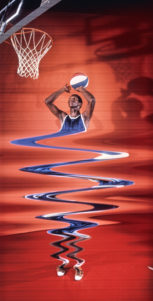

Tiny Archibald, 1972

Tiny Archibald, 1972

Tiny Archibald, 1972

Close Close Read MoreThe following excerpt is from Masters of Contemporary Photography Zimmerman & Kauffman Photographing Sports.

Zimmerman was aksed by an editor at Sports Illustrated to do an essay on baskeball players Julius Erving, Pete Maravich, Willy Wise and Nate Archibald. Each had a unique attribute that made them star play-makers. With the help of the editor Zimmerman defined what it was, but when it came to intrepreting it in pictures he had to rely on his technical skills alone.

Another type of slit camera, manufactured by Panon, does not transport the film past the lens. Instead, as with the Widelux and several other cameras, the lens itself moves. The effect is quite different from all other cameras. Nate (Tiny) Archibald, a relative midget among the giants of the game, survives on his ability to rise to the occasion with a deadly outside shot.

What Zimmerman wanted to create was an impresion of the twisting lower half of Archibald’s body zigging and zagging as he headed up towards the basket. The photographer held the camera vertical and moved it back and forth during the lens sweep, thereby imparting the contorted image of the lower half of Archibald’s body. As he was nearing the basket, Zimmerman steadied the camera. Basket, ball, and the upper torso and head appear undistorted. Seamless paper had to be stretched across the entire background and Zimmerman modified the shutter, slowing it down so as to have more time in which to perform his precise manipulations.

-

Greyhounds, 1961

Greyhounds, 1961

Greyhounds, 1961

Close Close Read MoreThe following excerpt is from Masters of Contemporary Photography Zimmerman & Kauffman Photographing Sports.

At a Phoenix, Arizona track, John Zimmerman (for Sports Illustrated) set up two Ascor 800 series strobes on the track lighthing fixtures to illuminate the dogs, and four Ascor 600 series strobes on other light stands aimed at the crowd. Trip cords were suspended over the track to the camera, a Hexacon Supreme with 180mm Sonnar lens. The camera was one of the first motorized models, now unavailable, and film was old style Kodachrome 10. John explains, “I determined that the most dramatic pictures were not of the first dog of the pack, but after he had passed, throwing sand in his wake, you see the following dogs coming through it.”

-

Javelin, 1972

Javelin, 1972